As the coronavirus pandemic approaches the end of a second year, the United States stands on the cusp of surpassing 800,000 deaths from the virus, and no group has suffered more than older Americans. All along, older people have been known to be more vulnerable, but the scale of loss is only now coming into full view.

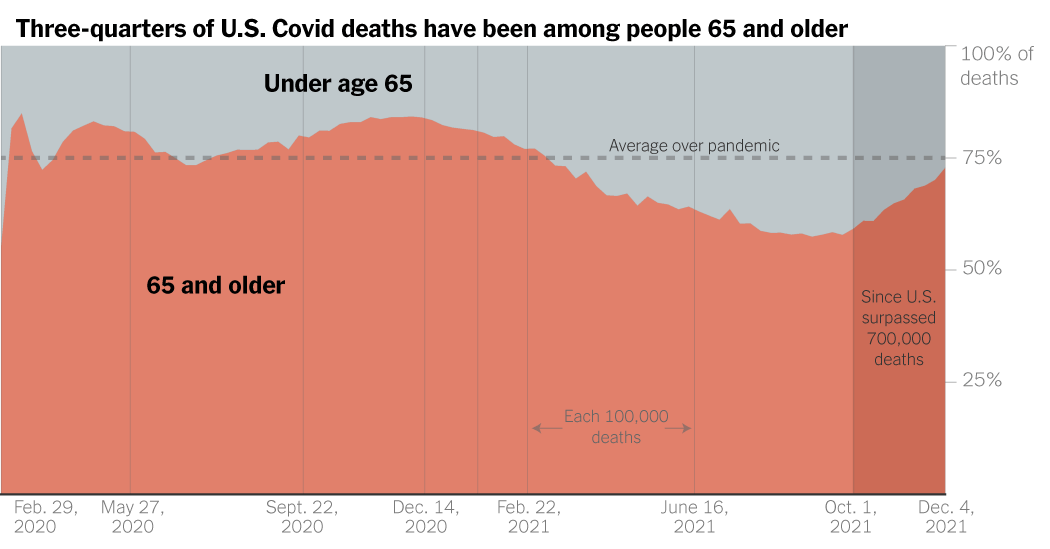

Seventy-five percent of people who have died of the virus in the United States — or about 600,000 of the nearly 800,000 who have perished so far — have been 65 or older. One in 100 older Americans has died from the virus. For people younger than 65, that ratio is closer to 1 in 1,400.

The heightened risk for older people has dominated life for many, partly as friends and family try to protect them. “You get kind of forgotten,” said Pat Hayashi, 65, of San Francisco. “In the pandemic, the isolation and the loneliness got worse. We lost our freedom and we lost our services.”

Since vaccines first became available a year ago, older Americans have been vaccinated at a much higher rate than younger age groups and yet the brutal toll on them has persisted. The share of younger people among all virus deaths in the United States increased this year, but, in the last two months, the portion of older people has risen once again, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. More than 1,200 people in the United States are dying from Covid-19 each day, most of them 65 or older.

In both sharp and subtle ways, the pandemic has amplified an existing divide between older and younger Americans.

In interviews across the country, older Americans say that they have continued to endure the isolation and fear associated with the pandemic long after tens of millions of younger and middle-aged people have gone back to work and school and largely resumed normal lives. Older people are still falling seriously ill in great numbers, particularly if they are unvaccinated, and hospitals in the Midwest, New England and the Southwest have been strained with an influx of patients this month. Worried about their risks, and the ongoing warnings from health officials about the added dangers for older people, many of them are still curtailing travel and visits with grandchildren, and are dining out less.

“After seeing a couple of people we knew die, we weren’t going to take any chances at all,” Rob Eiring, 70, a semiretired sales executive in Mill Creek, Wash., said of the way he and his wife had responded to the pandemic. “We really retreated. Everything turned inward for us.”

The relentless waves of new threats — a surge of the Delta variant and now the new Omicron variant — have been especially stressful for older Americans, prompting some people to consider tightening restrictions on their lives even more, during a period of life when socializing and staying physically and mentally active is considered essential.

“People are worried right now,” said Ann Cunningham, 84, who lives in a high-rise designated for seniors in Chicago, where a television room and a community room have remained shut down since March 2020. “If you’ve been inside for a long time, and the only time you talk to somebody is to get your mail or go down to the deli, that is a lot of isolation and loneliness for some people. They feel like nobody in the world cares for them.”

At the same time, the push by many companies to have employees return to workplaces is also creating new tension for adults who are older — but still working — and considered at higher risk if they were to get the virus, some experts said. “There’s all these ways — subtle, overt, direct, indirect — that we are not taking the needs of older people in this pandemic into account,” said Louise Aronson, a geriatrician at the University of California, San Francisco, and author of “Elderhood.”

The pandemic is no longer in the early, dark days of spring 2020, when the mysterious virus was sweeping through nursing homes and assisted living facilities and killing people in staggeringly high numbers, particularly those with pre-existing health issues.

After the first known coronavirus death in the United States in February 2020, the virus’s death toll in this country reached 100,000 people in only three months. The pace of deaths slowed throughout summer 2020, then quickened throughout the fall and winter, and then slowed again this spring and summer.

Throughout the summer, most people dying from the virus were concentrated in the South. But the most recent 100,000 deaths — beginning in early October — have spread out across the nation, in a broad belt across the middle of the country from Pennsylvania to Texas, the Mountain West and Michigan.

These most recent 100,000 deaths, too, have all occurred in less than 11 weeks, a sign that the pace of deaths is moving more quickly once again — faster than at any time other than last winter’s surge.

By now, Covid-19 has become the third leading cause of death among Americans 65 and older, after heart disease and cancer. It is responsible for about 13 percent of all deaths in that age group since the beginning of 2020, more than diabetes, accidents, Alzheimer’s disease or dementia.

The virus deaths of older people have sometimes been dismissed as losses that might have occurred anyway, from other causes, but analyses of “excess deaths” challenge that suggestion. Eighteen percent more older people died of all causes in 2020 than would have died in an ordinary year, according to data from the C.D.C.

“You can say, ‘They would have died anyway’ about any death, because we’re not immortal,” said Andrew Noymer, an associate professor of public health at the University of California, Irvine. “The point is you’re multiplying years of life lost by hundreds of thousands of deaths.’’

A year ago, when public health officials in this country began rolling out vaccines against the virus, they made older Americans a priority for shots before most younger people. Older Americans are now the most vaccinated age group in the country: 87 percent of people 65 and older have been fully vaccinated, according to the C.D.C.

Still, many older people who are unvaccinated have died of the virus. And the natural weakening of immune systems and organ function, geriatricians say, leave even vaccinated older people more vulnerable. The most recent available C.D.C. data on deaths among vaccinated people, which does not include those in the past 10 weeks, shows breakthrough deaths to be a small fraction of the nation’s toll. But there is no doubt that breakthrough infections in older people have resulted in some deaths.

Helen Safranek, 68, of Venice, Fla., said her husband, Marc, who was 70, had been fully vaccinated and had received a booster shot three weeks before he became sick with the virus and died in October.

The Coronavirus Pandemic: Key Things to Know

Pfizer’s Covid pill. A study of Pfizer’s oral Covid treatment confirmed that it helps stave off severe disease, even from the Omicron variant, the company announced. Pfizer said the treatment reduced the risk of hospitalization and death by 89 percent if given within three days of the onset of symptoms.

The couple wore masks everywhere, she said, but had felt secure enough after the booster shots to join in card games with other residents of their retirement community. Mr. Safranek had other health problems, including diabetes, but felt assured that even a breakthrough Covid infection would be mild.

“We did everything they told us to,’’ Ms. Safranek said.

For much of this year, concerns related to the pandemic shifted to the safety of college campuses, workplaces, schools and children too young to qualify for vaccination — even though it was older Americans who were still most at risk from the virus. Throughout the pandemic, some older people said they had often felt that their own autonomy and health were deemed less important than restarting the economy, reflected in headlines like one in Time magazine in May 2020: “The Road to Recovery: How Targeted Lockdowns for Seniors Can Help the U.S. Reopen.”

“The fact that we’re so concerned about school and school kids and child care, and older people have dropped to the side, it’s just more evidence of our pervasive ageism in our society,” said Elizabeth Dugan, an associate professor of gerontology at the University of Massachusetts Boston.

At the same time, some older people who have spent decades shrugging off traditional notions of age have chafed at the notion that they personally belong to an at-risk group at all, or that people 65 and older can be lumped together. Throughout the pandemic, Billy Simmons, a 71-year-old organic farmer in central Iowa, said that he had not taken public health warnings about his age too seriously, reasoning that he rarely gets sick, never sits around watching television and has been a vegetarian throughout his life.

Mr. Simmons, who decided not to be vaccinated, said he does not pay attention to the public health guidance that people who are older are more vulnerable in the pandemic. “I’m a lot healthier than people I know who are 20 years younger than me,” he said. “I don’t think they talk enough about your level of stamina and healthiness. If you’re 65 and older but very healthy and you eat well and you don’t oversleep, then you might not have so much to be concerned about it.”

Hollis Davenport, who lives on the West Side of Chicago, said that the pandemic had not been difficult to endure, especially when he considers that he no longer has the problems that younger, working people have.

“I used to worry about paying a telephone bill,” said Mr. Davenport, who spends most of his time at home, reading the news or listening to jazz on the radio. “Now I sit here and I meditate and I think about all the things I’ve done, and I get a big laugh. What am I afraid of, at 86?”

But for many, the heightened vulnerability tied to age has forced new discussions about mortality — about peers who have died of the virus, about end-of-life plans and about the swift passage of time.

Simone Mitchell-Peterson, chief executive of the Chicago chapter of Little Brothers — Friends of the Elderly, said that at this point in the pandemic, she could detect a difference in the physical appearance of people her group works with.

“You can see the frailty of our elders,” she said. “Many of them have lost weight. Many of them just look older. Their stoop is a little more pronounced.”

Patt Schroeder, 79, of Oakland, Calif., is one of the millions of older people who soldiered through the pandemic staying active: attending weekly Zoom meetings, including one on racial justice run by her church and another with a loose-knit group of her friends and colleagues who call themselves “The Lovely Ladies.”

They agree that life during the pandemic has been stressful for older adults. But on a recent Friday, their concern turned to the plight of younger Americans.

“Those of us who are older, we know how to keep on keeping on,’’ Ms. Schroeder said.