Carvana

ILLUSTRATION BY STEPHANIE JONES FOR FORBES; PHOTO BY MARK RALSTON/AFP via Getty

After letting go 2,500 people, or 12% of its workforce, the online used car seller Carvana faces a moment of reckoning.

On Friday, May 6, Michelle, a recruiter at online used car retailer Carvana, was told her job was safe, despite the company’s recent freeze on new hiring, which had put her team “on pins and needles.” Four days later, on Tuesday, May 10, Carvana CEO Ernie Garcia III sent a company-wide email blast at 7:08 a.m Pacific Time, announcing that 2,500 people – 12% of the staff – would be let go. Shortly after, staff got invitations to a number of different meetings, many on Zoom. Whether they were in or out of their jobs wasn’t clear until those meetings. Michelle found out on Zoom, despite earlier assurances, that she was let go. “Obviously, it left a sour taste in my mouth,” says Michelle (who asked that Forbes only publish her middle name).

Others weren’t so lucky. Some say they were informed via pre-recorded messages. (The company denies it). Either way there were plenty of snafus. “Many people experienced extensive tech glitches with the Zoom, so they weren’t let into the meeting until the end. People were so lost and had to reach out to leadership to confirm if they were fired or not,” another laid-off employee told Forbes. Those invited who couldn’t get in “watched the chaos unfold on Slack,” echoed a third. The whole process “was kind of chaotic,” said Megan Thompson, an associate recruiter who was let go.

To top it off, Carvana had issued a press release less than three hours earlier touting the completion of its $2.2 billion acquisition of car seller Adesa’s vehicle auction business, snapping up its 56 U.S. locations—and its 4,500 employees. The irony wasn’t lost on those laid off. “The cherry on top,” said one recruiter who lost her job. “At least pick a different day,” scoffed Thompson.

Carvana says the layoffs were necessary due to a recession in automotive retail. “Saying goodbye to any team member is not a decision we take lightly and we aim to be transparent, thoughtful and supportive throughout this process,” said a Carvana spokesperson.

Indeed, Carvana’s mass firing was a sign of much bigger problems at the company, according to 10 former employees (most of whom spoke on the condition of anonymity) and several industry analysts. They describe a spendthrift business, whose growth-at-all-costs mentality undermined business operations and sowed the seeds of its recent layoffs.

“It always seemed like no one ever had a real game plan or reasoning behind the decisions they made when it came to policy changes or additional training,” said one former call center worker. “It was always just someone’s quick idea and that would be put into place with no additional planning.”

Ernie Garcia III, founder and chief executive officer of Carvana Co., second left, and his father Ernest Garcia II, chairman of Carvana Co., center, stand during the company’s initial public offering (IPO) on the floor of the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) in New York, U.S., on Friday, April 28, 2017. U.S. stocks remained near record highs, Treasuries dropped and oil closed in on $50 a barrel even after the world’s biggest economy reported its slowest pace of expansion in three years. Photographer:

Michael Nagle/Bloomberg

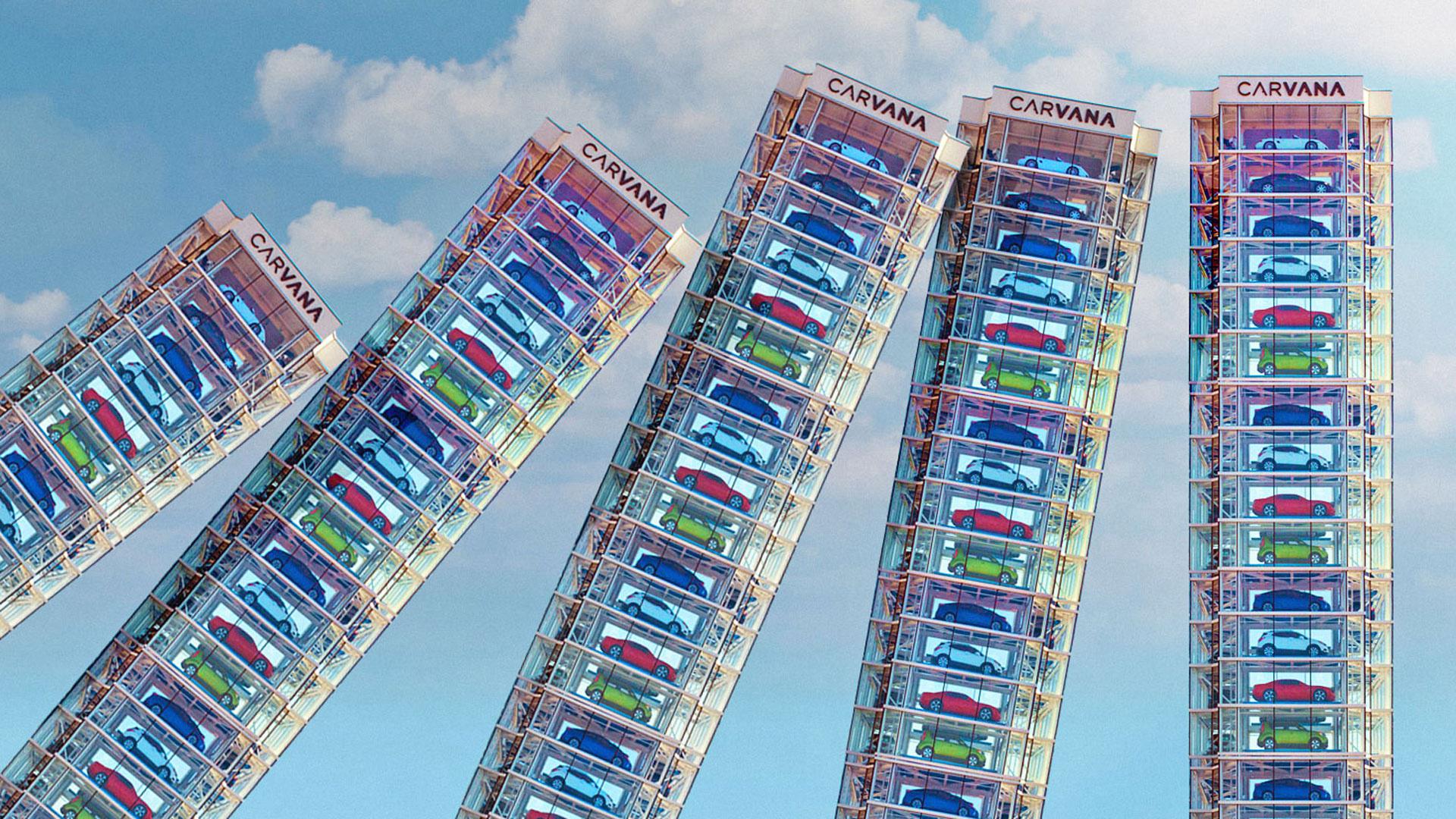

Behind the mess is a father-son duo who became billionaires riding Carvana’s lightning fast growth to an IPO, and who maintain a tight grip over the company. Ernie Garcia III started Carvana in 2012 as the e-commerce division of DriveTime, the used car and loan business run by his dad, Ernie Garcia II. For years, Carvana’s disruptive online business, flashy car vending machines and growth-over-profits mentality made it seem more of a Silicon Valley marvel than a used car dealer with clever marketing and fundraising savvy.

For Garcia senior, the IPO was particularly sweet, capping his decades-long comeback and public rehabilitation. In 1990, a 33-year-old Garcia pled guilty to a bank fraud charge related to his dealings with Lincoln Savings & Loan, which was controlled by Charles Keating. The thrift’s failure set off a political firestorm because of Keating’s connections with five U.S. senators, including John McCain. Garcia was sentenced to three years of probation, after agreeing to cooperate with U.S. prosecutors.

Today, the Garcias (who are worth a combined $5.3 billion, down from $23.3 billion last summer) control nearly 100% of the voting rights, thanks to a dual-class share structure that gives them outsized voting power. The company’s ownership structure creates conflicts of interest that “may result in decisions that are not in the best interests of stockholders,” the company states in its annual 10-K filing.

The business did thrive during the pandemic, as homebound consumers snapped up vehicles with stimulus checks and low-cost financing, while the chip shortage restricted supply of new cars and spiked demand for used cars. Carvana’s other business—originating and selling car loans—benefitted from the near-zero interest rate climate. In 2021, Carvana’s annual revenue doubled to $12.8 billion, from $5.8 billion in 2020 and $3.9 billion in 2019. Its stock climbed 330% from its March 2020 low to a record high of $370 last August. “With our progress so far this year, we believe our path to becoming the largest and most profitable retailer has never been clearer,” the company boasted in a note to shareholders last August after reporting $45 million in net income for second quarter 2021 earnings—the company’s first, and only, profitable quarter.

As car sales took off, Carvana increased its headcount and footprint. At the beginning of 2021, it employed 10,400 people; a year later, 21,000. In that time Carvana also rolled out operations in at least 45 new cities and states and signed a 10-year, $162 million lease for around 550,000 square feet of office space in Atlanta’s State Farm building. But former employees say that rapid expansion came with a price: high turnover and lack of preparation in the operations department, which led to delivery delays, cancellations and failure to get customers the paperwork they needed to legally drive their cars.

“We would have people angry that they have these undriveable cars, not because anything’s wrong with the cars, but because of the bureaucratic process that it takes to register a vehicle,” says one former Carvana accountant. “That was always a problem. Always.”

CARVANA’S PANDEMIC PERFORMANCE

One laid-off car delivery driver told Forbes that newly hired customer service reps struggled to manage vehicle titles and varying state laws on car registrations: “We [the drivers] would have to face the wrath of customers because we were telling them they needed documents that, if they had a delivery over the weekend, they couldn’t get because their agents weren’t in.”

Similar claims form the basis of a recent class action lawsuit filed against Carvana in Pennsylvania. That suit alleges that Carvana violated Pennsylvania’s Unfair and Deceptive Trade Practices Act by issuing temporary registrations and improperly collecting registration and licensing fees. “Carvana’s failure to timely register the cars as it promised and received money to do — sometimes for a period exceeding two years — causes consumers to be questioned and sometimes arrested by law enforcement while driving the temporarily registered cars,” the lawsuit states.

“We’ve been flooded with phone calls,” says Phillip Robinson, one of the two attorneys who filed the lawsuit, and says over 200 Carvana customers have gotten in touch. “People don’t know where to go to get help.”

Carvana denies any liability, contends that the allegations are without merit and is moving to enforce private arbitration.

On May 10, the Illinois Secretary of State suspended Carvana’s dealer’s license due to “misuse of issuing out-of-state temporary registration permits and for failing to transfer titles,” Henry Haupt, Illinois Secretary of State spokesman, told Forbes over email. The order prevents Carvana from selling vehicles in Illinois (though vehicles that have already been purchased, but not yet delivered, can still be delivered to the buyers). “The suspension will remain in place until the issues are resolved,” Haupt says. Carvana, which “strongly disagrees with the state’s characterization of both the facts and the late leading to this action,” says it is actively working with Illinois to resolve the issue. North Carolina had banned Carvana last year for failure to deliver titles and conduct state-required inspections. It was lifted after six months.

A former Carvana car hauler added that the company failed to provide enough trucks to complete deliveries, and that, as a result, customers were sometimes asked to pick up their new cars—or, Carvana employees drove the purchased cars to their customers. “The company a lot of times prioritized getting more bodies in the company to prepare for future sales growth, [rather] than actually building the infrastructure to handle that type of sales volume,” the ex-employee said.

Another big problem was the fact that it brought on too many people, too fast, according to some former employees. “The biggest expense and error I saw was simply the amount of hiring we were doing,” said a laid-off training coach, who coached new customer services hires and whose team ballooned from 30 people to 150 over the last year. “It was definitely an over-hiring problem.”

Carvana’s operations department, which was tasked with completing the actual car deliveries (and where the majority of last week’s layoffs occurred), “was always fluffy” and had “fat to trim,” said the former accountant. “But then they’d just replace those people. It didn’t make sense because they wouldn’t just pay people a good salary to stay there and learn and do a great job. They would just throw bodies at stuff.”

A Carvana used car “vending machine” on May 11, 2022 in Miami, Florida. Carvana Co. announced it is letting go about 2,500 workers, a few weeks after the company posted a $506 million loss in the first quarter.

Joe Raedle/Getty Images

There was plenty of chaos elsewhere at the company. “There wasn’t any assigned seating or real tracking of tech equipment so stuff would go missing all the time,” said one former employee about Carvana’s Tempe, Arizona campus. Another former customer services trainer added: “Employees would come to pick up new work-from-home equipment, and there would be piles of computers and monitors in corners in the buildings. The company did not care about loss or waste, including the technology.”

2022 has been a rude wakeup call. Inflation has hit the business hard, as prices for both used cars and gas have lowered demand from would-be car buyers. Rising interest rates have also made buying a car more expensive—and weighed on Carvana’s loans securitization business, which before had padded the company’s gross profitability. “Carvana is getting hit much harder with the rise in rates than your typical car dealer, because they are relying on that financing flow to feed their business, and that is obviously very interest rate sensitive,” says Daniel Taylor, an accounting professor at the Wharton School, who compares Carvana to a subprime mortgage lender during the 2000s housing bubble. “You sell houses for the purposes of originating mortgages and then distributing those mortgages to investors. Carvana is in the originator distributor business—originating car loans and selling those loans is its primary business.”

During last month’s earnings call, Garcia III acknowledged that Carvana’s return to financial health depended, in part, on financial adjustments that would “reduce the impact of rapidly rising rates on GPU [gross profit per unit] until we return to an environment with more stable rates.” Michael Jenkins, Carvana’s chief financial officer, added that the rapid rise in interest rates was weighing on the firm’s profitability.

Last month, Carvana reported its first-ever quarter-over-quarter decrease in revenue, and a net loss of $506 million for the first quarter—an amount greater than its previous five quarterly losses combined. No question, Carvana had relied on numerous financing rounds to fund its growth. Between January 2020 and now, it raised over $8.8 billion through debt offerings and equity sales, Forbes calculates. Last month’s nearly $3.3 billion bond sale—to help finance Carvana’s acquisition of Adesa as well as to fund what it said were “general corporate purposes”—came with a hefty 10.25% annual coupon payment.

“The company seems a classic case of growing so quickly to handle revenue expansion that optimization and efficiency take a backseat,” says Michael Ashley Schulman, chief investment officer at Running Point Capital Advisors, an investment firm for family offices that doesn’t own the stock. “Carvana could have better managed costs and minimized losses by reigning in its own topline growth.”

All of this has sent Carvana’s stock crashing, down 91% from its peak last August. As of Thursday’s close the younger Garcia was worth around $800 million, Forbes estimates, a far-cry from his $7.4 billion fortune last summer. His father, Garcia II, who bankrolled the company’s early growth and is Carvana’s largest shareholder (but holds no formal title at the company), has a net worth of $4.5 billion—down from a high of $15.9 billion last summer, but more than he would have been worth if not for his well-timed stock sales: He unloaded nearly $3.6 billion (pre-tax) worth of Carvana stock, including around $2.35 billion worth of stock in 2021 and another $1.15 billion in the last quarter of 2020. The father-son team did pick up roughly $430 million worth of shares in April in a $1 billion stock sale meant to help finance Carvana’s Adesa acquisition and other general business purposes. Those shares have already lost more than half their value.

A new era for Carvana—one of belt tightening—has arrived. In a note to investors on May 13, Carvana disclosed that its recent layoffs will save an estimated $125 million annually. The company has promised to further reduce expenses and boost profitability. It said the Adesa acquisition “will ultimately prove to be a pivotal moment on our path to becoming the nation’s largest and most profitable automotive retailer.”

Or, the acquisition could make Carvana a more attractive merger or acquisition target, says Dick Pfister, CEO of AlphaCore Wealth Advisory, who has been bearish on the stock. Adesa and its assets “gives Carvana some quality on their balance sheet,” Pfister says.

For investors who bought Carvana late into the cycle, any merger may well be a money-losing deal. Still, at least some are not surprised.

“What I’m saying is the Garcias knew it was short-lived,” says Wharton School professor Daniel Taylor. “The Garcias knew the music would eventually end.”