SAGINAW, Mich. — On the top floor of the hospital, in the unit that houses the sickest Covid-19 patients, 13 of the 14 beds were occupied. In the one empty room, a person had just died.

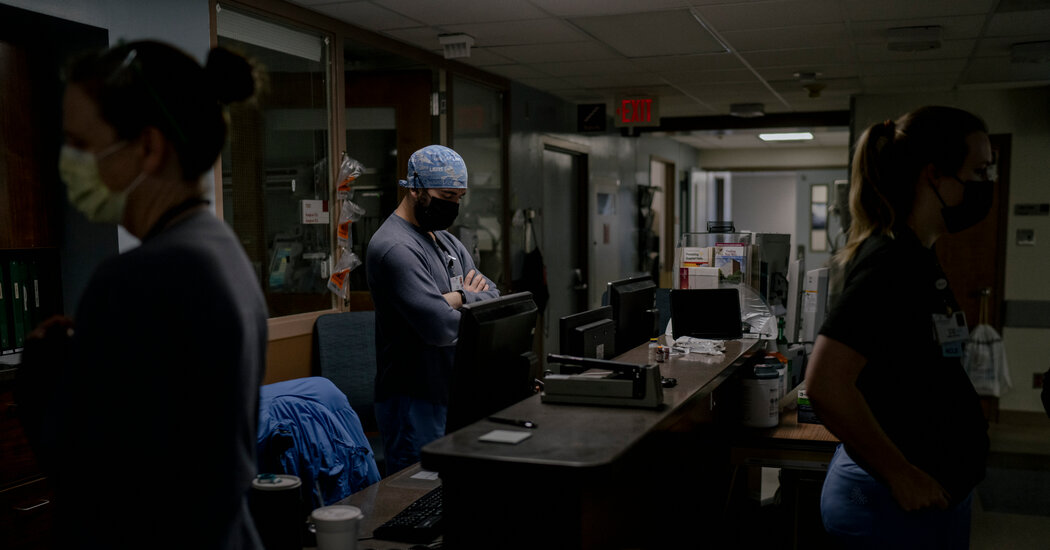

Through surge after surge, caregivers in the unit at Covenant HealthCare in Saginaw, Mich., have helped ailing patients say goodbye to their relatives on video calls. The medical workers have cried in the dimly lit hallways. They have seen caseloads wane, only to watch beds fill up again. Mostly, they have learned to fear the worst.

“You come back to work and you ask who died,” said Bridget Klingenberg, an intensive care nurse at Covenant, where staff levels are so strained that the Defense Department recently sent reinforcements. “I don’t think people understand the toll that that takes unless you’ve actually done it.”

The highly contagious Omicron variant arrives in the United States at a moment when there is little capacity left in hospitals, especially in the Midwest and Northeast, where case rates are the highest, and where many health care workers are still contending with the Delta variant. Some researchers are hopeful that Omicron may cause less severe disease than Delta, but health officials still worry that the new variant could send a medical system already under pressure to the breaking point.

About 1,300 Americans are dying from the coronavirus each day. The national case, death and hospitalization rates remain well below those seen last winter, before vaccines were widely available. But suddenly, positive tests are growing. State officials in New York reported more than 20,000 coronavirus cases on Friday, which they said was more than on any other day of the pandemic. In Connecticut and Maine, reports of new infections have grown by around 150 percent in the last two weeks. In Ohio and Indiana, hospitalization rates are approaching those seen during last winter’s devastating wave.

“Living in a constant crisis for 20 months-plus is a little overwhelming,” said Dr. Matthew Deibel, the medical director for emergency care at Covenant, where patients must sometimes wait hours to be seen because of a shortage of beds and staff.

With coronavirus hospitalizations increasing 20 percent nationally over the last two weeks, to 68,000 people, doctors and nurses are speaking with renewed alarm about conditions and pleading with people to get vaccinated.

In Minnesota, several hospital systems released a joint message saying that employees were demoralized and that “your access to health care is being seriously threatened” by the pandemic. In Rhode Island, Gov. Dan McKee wrote a letter to federal officials asking for staffing help, noting that “hospitals are reporting that their emergency departments are at capacity and that patients are leaving without being evaluated.” In Nebraska, a hospital released a video showing a nurse fielding three requests to care for critically ill virus patients, but having beds for only two of them. On Friday, Gov. Mike DeWine of Ohio mobilized more than 1,000 National Guard members to help with hospital staffing.

The outlook is especially troubling in Michigan, which has the highest coronavirus hospitalization rate in the country. About 4,700 virus patients were hospitalized statewide this week, more than had been recorded during the state’s three previous spikes. And though daily case reports have dropped slightly from the record highs seen before Thanksgiving, more than 6,500 people in Michigan continue to test positive for the virus each day.

At Covenant, there are fewer coronavirus patients than last winter, but limited staffing and a return of patients who delayed care for chronic issues during the pandemic have diminished resources.

Earlier this week, about 100 patients in the sprawling hospital had active or recently resolved coronavirus infections. Of the 68 patients whose infections were still active, about 70 percent were unvaccinated, hospital officials said. Among the vaccinated patients, only two had received a booster shot.

With Omicron, breakthrough infections are common, but scientists believe that the vaccines will still provide protection against the worst outcomes. Booster doses are likely to provide additional protection against infection, preliminary data suggests.

In Saginaw, doctors and nurses said they have noticed colleagues struggling with the relentless nature of the pandemic — with fatigue, short tempers, post-traumatic stress, and with frustration toward the unvaccinated.

A handful of states led by Democrats have reimposed some restrictions in recent days, including new mask rules in California and New York. But in many places, normal life continues and there appears to be limited appetite for new restrictions, even if cases rise.

Some school districts have dropped mask mandates in recent days, and federal officials expect Christmas air travel to approach prepandemic levels. Unlike last year, few health directors have told people, especially those who are vaccinated, to skip holiday gatherings.

Around Saginaw, a city of about 44,000 residents that is 90 minutes north of Detroit, medical workers said it could sometimes feel that their neighbors have overlooked the pandemic. Mask usage is spotty. Large events have resumed. In Saginaw County, about 50 percent of people are considered fully vaccinated, a figure that does not include booster shots. That rate is below Michigan’s average, which is below the national rate of 61 percent.

If people saw what they did every day, many workers in Covenant’s Covid ward said, they might behave differently.

“Unless you are up in that unit working side by side with me seeing the true devastation of the virus and what it physically does to the human body, how can you appreciate it? How?” said Jamie Vinson-Hunter, a respiratory therapist.

It was almost exactly a year ago when doctors and nurses at Covenant and other hospitals were among the first people to get a coronavirus vaccine. For many of them, it was a moment of optimism when it seemed that the emergency response to the coronavirus might soon end. For a time, it seemed possible: For one day in June, there were no patients at Covenant with active coronavirus infections.

The Coronavirus Pandemic: Key Things to Know

Since then, the picture has worsened significantly. The immunity from those first vaccines may be on the wane. While recent data on breakthrough cases and deaths for all Americans is not readily available, recent federal data from nursing homes shows a sharp uptick in cases among people who were fully vaccinated but had not yet gotten a booster shot.

To see how far things have devolved in Saginaw, one needs only to spend time on the seventh floor of Covenant. There, in a slender hallway with a low ceiling, nurses buzz in and out of rooms. The floor is busy but not panicky, with the whirring and beeping of machines making up most of the soundtrack. Many of the sick are sedated and on ventilators, unable to speak with their doctors. Others are confused.

“This illness is dehumanizing,” said Dr. Amjad Nader, who cares for people in that unit. He added, “Sometimes I don’t see light in the eyes of my patients.”

Many of the caregivers on that floor have become virus experts. They talk about the satisfaction of calling a patient’s spouse if the patient no longer needs a ventilator after weeks of treatment. They lament the frustration of having no cure. They grieve every time they lose a patient.

Ms. Klingenberg, the nurse, volunteered to work with coronavirus patients at the start of the pandemic and has passed up opportunities to take other assignments.

“Mostly, it’s for my co-workers,” she said. “I don’t want to quit on them. And somebody has to do it. And we’re apparently the people who have chosen to do it.”

But the pandemic was not something she could leave at work. Family members tested positive. Early this year, when Ms. Klingenberg was 26 weeks pregnant, she tested positive too.

Unlike most women in their 20s, she had a severe case and was hospitalized at the University of Michigan. For a time, she faced the possibility of intubation. Then, after about a week, she started to improve. She was able to go home. Her baby was healthy and did not have to be delivered early.

The experience and the fear, she said, now helps her connect with her patients getting the same breathing treatments she received months ago.

“They have these moments of distress because this mass is strapped onto you, you can’t take it off, it’s pushing air into your lungs,” Ms. Klingenberg said. “Your natural reaction is to fight against that. So I can help, I feel like, calm them down and tell them exactly: ‘I understand what this feels like. I know exactly what you’re going through.’”

At other moments, she said, the trauma and the relentlessness of the pandemic — wave after wave — feel like too much.

“I’ll be taking care of these patients and all of a sudden I’ll be right back at U. of M., and I get flashbacks sometimes,” she said. “So I’m still trying to heal from that almost-near-death experience. And then I came right back to Covid, which was my choice. But it’s a little scary.”

Lola Fadulu contributed reporting.