A C.D.C. study suggests that 42 percent of children aged 5 to 11 have coronavirus antibodies from prior infection, prompting some F.D.A. advisers to ask if one dose would be sufficient for children. Use of that study has been questioned by some scientists. F.D.A. panelists also asked whether only those with high-risk medical conditions, such as obesity, should get the vaccine, since it is clear they are most vulnerable to getting very ill with Covid-19.

But C.D.C. officials said it would be hard to narrow eligibility, and the F.D.A.’s advisory panel endorsed offering the pediatric dose to the entire age group by a 17-0 vote, with one abstention.

Dr. Marks, the F.D.A. regulator, said on Friday that data on vaccinating children younger than 5, which Pfizer and Moderna are currently studying, were a “few more months off.”

“The benefit-risk gets to be even more of a careful consideration, because the youngest children are affected the least directly in terms of severe Covid-19,” he said.

Dr. Snowden said the Delta variant wiped out any notion that children are impervious to the virus. At the height of the most recent surge, she said, the Arkansas Children’s Hospital was treating as many as 30 children a day for Covid, including some with fully vaccinated parents. While that number has shrunk, “it is still not back to where we were before Delta,” she said.

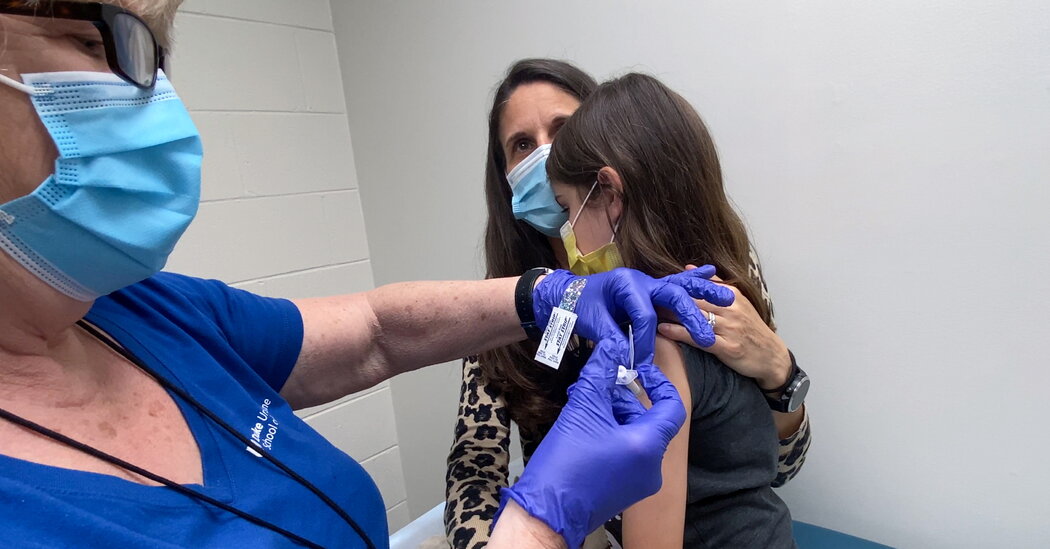

Much of the burden of the rollout of children’s shots is expected to fall on pediatricians and family physicians, many of whom are strained by staffing shortages and pent-up demand for care at this point in the pandemic but have deep relationships with parents and children. Dr. Sterling Ransone, the president of the American Academy of Family Physicians and a physician in rural Deltaville, Va., said that he would keep his office open later on weekdays and on Saturdays to accommodate demand for pediatric shots.

“We know who to prioritize — asthmatics, those with heart disease, people who are obese,” he said.

Dr. Victor Peralta, a pediatrician in the racially diverse neighborhood of Jackson Heights, Queens, said uptake might be a bit slower at first among his patients, most of whom are poor enough to have Medicaid coverage. But he predicted the pediatric dose would catch on and ultimately help slow transmission of the virus. “I have no doubt that this will make a difference beyond just the worried well,” he said.