Economist Richard Easterlin died a number of weeks in the past. Throughout 1974, as a scholar on the College of Pennsylvania, he printed the benchmark examine on cash and happiness. He lived lengthy sufficient to see his conclusions challenged and to defend them.

The Easterlin Paradox

Way back, Dr. Easterlin instructed us that after our fundamental wants are happy, extra earnings past $75,000 brings no extra happiness:

Extra just lately, he additional defined

“Even though I’m happier because my income is higher, I’m less happy because everyone else is going up too…So the result is, because of social comparison, people fail to enjoy improvement in income as a source of happiness.”

Different Research

Kahneman and Deaton

In one other paper (2010), Nobel laureates Daniel Kahneman and Angus Deaton concluded that we plateau someplace between $60,000 and $90,000. As earnings rises to as a lot as $90,000, we get happier. After although, incomes extra, we really feel no higher.

Killingsworth

Then, additional complicating the solutions, we’ve had a College of Pennsylvania researcher reporting that extra earnings correlated with extra happiness. Utilizing his “Track Your Happiness” app, Matthew Killingsworth had members categorical how pleased they felt at random occasions through the day. When the app “pinged,” they needed to reply questions that included their place on a “very good” to “very bad.” emotions scale.

These had been the Killingsworth conclusions:

Then, to all of this, we are able to add nonetheless extra analysis

Kahneman and Killingsworth

Making an attempt to determine if we do or don’t plateau, Kahneman and Killingsworth noticed a cheerful group and people which might be sad. The pleased folks proceed feeling higher as their wealth ascends. However the people which have extra disappointment tendencies are positively affected till annual earnings hits $100,000. After which, they’re those that plateau.

Or, as Dr. Killingsworth defined, “…if you’re rich and miserable, more money won’t help. For everyone else, more money was associated with higher happiness to somewhat varying degrees.” Including extra element, the arbiter of the examine stated, “…For those in the middle range of emotional well-being, happiness increases linearly with income, and for the happiest group the association actually accelerates above $100,000.”

Blanchflower

In the meantime, economist David Blanchflower checked out age. Asking how our happiness modifications as we become older, he concluded that everybody is threatened by “peak misery” when they’re 47 or 48 years outdated. Gender seems to not matter. Neither does affluence or the GDP. Nevertheless it does rely in your nation. In developed nations the nadir is at age 47.2 while it happens a year later in developing countries.

Stevenson and Wolfers

With Stevenson and Wolfers, we need to take a baby step away from happiness to life satisfaction.

Calling their data a satisfaction ladder, people who live in countries with a higher per capita GDP tend to be more satisfied with their lives:

The Numbers

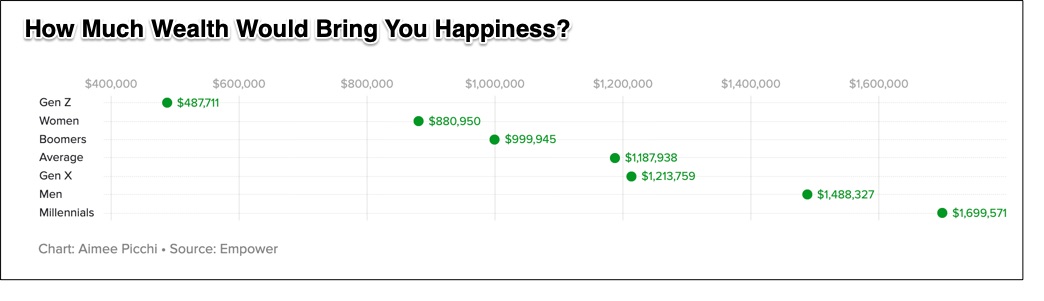

An Empower study actually gave us precise numbers:

Our Bottom Line: The Economic Significance of Happiness

At this point we should consider a 2023 NBER paper that includes why economists care about happiness. Explaining, they initially identify short-run happiness like elation and the long-run happiness of a baseline mood. Predictably, our short-term happiness provides information about our preferences (and I assume our demand). By contrast, looking at the long run takes us to policy issues.

But it all began with Richard Easterlin.

Below, in his 90’s, he looks back at his work:

My sources and extra: Right now’s replace summarizes and quotes a few of our econlife posts (together with right here and right here) from the previous decade. I additionally advocate this Easterlin obituary from the New York Occasions.