From late spring into early summer, Britain’s elementary and secondary schools were open during an alarming wave of Delta infections.

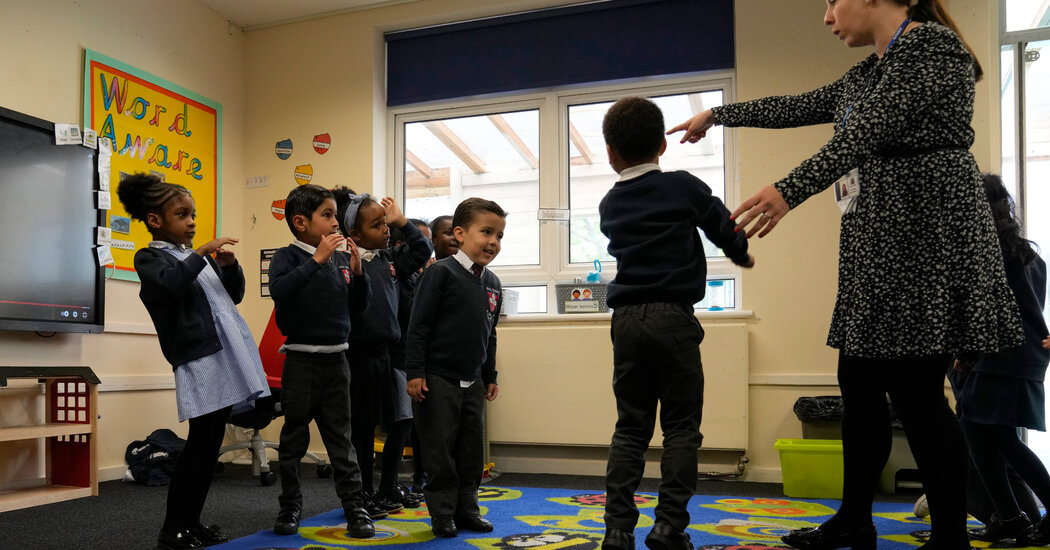

And they handled the Delta spike in ways that might surprise American parents, educators and lawmakers: Masking was a limited part of the strategy. In fact, for the most part, elementary school students and their teachers did not wear them in classrooms at all.

Instead, the British government focused on other safety measures, widespread quarantining and rapid testing.

“The U.K. has always, from the beginning, emphasized they do not see a place for face coverings for children if it’s avoidable,” said Dr. Shamez Ladhani, a pediatric infectious-disease specialist at St. George’s Hospital in London and an author of several government studies on the virus and schools.

The potential harms exceed the potential benefits, he said, because seeing faces is “important for the social development and interaction between people.”

The British school system is different than the American one. But with school systems all over the United States debating whether to require masking, Britain’s experience during the Delta surge does show what happened in a country that relied on another safety measure — quarantining — rather than face coverings for young children.

Unlike the United States, all public and private schools in England are expected to follow the national government’s virus mandates, and there is a single set of guidelines. (Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland are responsible for their own schools, but the rules have been similar.)

The Delta variant tested the guidelines. Starting in June, case numbers quickly increased before peaking in mid-July, which roughly mirrors the last few months of the school calendar. For the 13 million people in England under the age of 20, daily virus cases rose from about 600 in mid-May to 12,000 in mid-July, according to government data. Test positivity rates were highest among children and young adults — ages 5 to 24 — but they were also the least likely to be vaccinated.

It is difficult to pinpoint exactly how much spread occurred on campuses. But throughout the pandemic, government studies showed that infection rates in schools did not exceed those in the community at large, Dr. Ladhani said. In schools that experienced multiple virus cases, he added, there were often “multiple introductions” — meaning that infections were likely acquired outside the building.

There is debate about whether the end of the school year in mid-July contributed to the nation’s drop in virus cases, but some researchers point out that the decline began before schools closed.

To counter the Delta variant during the last academic year, the government provided free rapid tests to families and asked them to test their children at home twice per week, though compliance was spotty. Students were kept in groups within the school building and sent home for 10-day quarantines if a virus case was confirmed within the bubble. More than 90 percent of school staff members had received at least one vaccine dose by the end of June, according to a government sample survey of English schools, a similar vaccination rate to American teachers in the Northeast and West, but higher than in the South.

Under the government guidelines, masks in classrooms were required only for discrete periods in secondary schools, the equivalent of middle and high school, and were never required for elementary-age children.

And there was less partisan divide; both the Conservative and Labour Parties have generally believed that face coverings hinder young children’s ability to communicate, socialize and learn.

In England, schools followed government recommendations last academic year and aggressively quarantined students and staff who came into contact with the virus.

But quarantines were disruptive for students and parents and led, in mid-July, to more than 1 million children being forced out of schools, or 14 percent of the public school population. During the same period, about 7 percent of teachers were sent home.

Rudo Manokore-Addy, the mother of a 7-year-old and 3-year-old in London, described herself as more cautious when it came to the virus than the typical British parent. In the spring of 2020, she encouraged her daughters to wear cloth masks outside the house. At times last summer and this past winter, she kept both girls home from school to observe the schools’ virus policies before sending her children back.

Last spring, during the Delta surge, she and her husband gladly kept their children in school, unmasked.

“I was quite relaxed,” she said. “At the end, we just resolved to kind of go with it. We were confident the school had practices in place.”

In the United States, the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention currently recommends universal masking inside school buildings, and the C.D.C. has advised that breaches in mask use were likely responsible for some spread of Covid-19 in American schools.

This recommendation has been divisive, with nine states attempting to ban school mask orders, according to the Center on Reinventing Public Education, a think tank. But with low vaccination rates in many communities and limited access to regular virus testing across the country, masking may be one of the easiest safety measures for American schools to put into place. In addition, the C.D.C. has said that students who come into contact with the virus in schools do not need to quarantine if both individuals wore well-fitting masks.

The American conversation on masks is “so polarized,” said Alasdair Munro, a pediatric infectious-disease researcher at the University Hospital Southampton. “It seems to either be viewed as an essential, nonnegotiable imperative or a very harmful infringement upon individual liberty.”

Others in Britain would welcome masking. Dr. Deepti Gurdasani, an epidemiologist and senior lecturer at Queen Mary University of London, has spoken widely for stricter safety precautions in schools. She called the British government’s opposition to masking among children “ideological,” and said she looked with envy at the New York City school system’s policies around universal masking and the placement of two air purifiers in each classroom.

But there has also been quarantining in the United States, with some schools that have reopened for the new academic year temporarily closing classrooms over the past several weeks.

Research from Britain suggests that rapid testing might be an alternative. In a study conducted as the Delta variant spread, secondary schools and colleges in England were randomly assigned to quarantine or test.

One set of schools quarantined students and staff members who came into contact with positive Covid-19 cases. The other allowed those contacts to continue coming into the building, but with the requirement that they take a rapid virus test each day for one week; only those who tested positive would be sent home.

Though the daily testing regimen was challenging for some schools to carry out, the results were reassuring: In both the quarantine and test groups, less than 2 percent of the contacts tested positive for Covid-19.

Further reassuring evidence comes from testing antibodies of school staff members; positivity rates were the same or lower than adults in the community, suggesting that schools were not “hubs of infection,” according to Public Health England, a government agency.

Today, after long periods of shuttered classrooms, there is now a broad consensus in Britain that policies that keep children out of school are “extremely harmful in the long term,” Dr. Munro said.

The national Department for Education also announced last week that in the coming school year, no one under the age of 18 would be forced to quarantine after contact with a positive virus case, regardless of vaccination status. (In Britain, vaccines are approved for individuals 16 and over.)

Masks will not be required for any students or school staff, though they will be recommended in “enclosed and crowded spaces where you may come into contact with people you don’t normally meet,” such as public transit to and from school.

Some critics believe that the British government has been too quick to loosen safety measures inside schools.

Dr. Gurdasani said the lack of precautions this fall would increase the number of children infected and suffering the effects of long Covid.

“I am not advocating for school closures,” she said. “But I don’t want a generation of children disabled in the coming years.”

Robin Bevan, president of the National Education Union and a secondary school principal in Southend, east of London, said he found it curious that Britons regularly masked in supermarkets, but not in schools.

“All we are left with is opening the windows and washing hands,” he said. “That is the government position.”

School leaders have the latitude to continue to keep children in defined bubbles or pods to reduce transmission — a practice Mr. Bevan said he would like to keep.

Many parents say they are keeping calm.

“It felt like in the U.K., there was such political commitment to reopening,” said Bethan Roberts, 40, who felt confident returning her three children to in-person learning last spring and keeping them there during the Delta surge.

“It didn’t feel very controversial here,” she added. “And there were lots of exhausted parents who were just, like, ‘We can’t do this anymore.’”

Alicia Parlapiano contributed reporting.