PHILADELPHIA — Late at night on Sept. 30, 1965, Edward David White, 18, walked toward his family’s rowhouse in the West Philadelphia neighborhood after his shift at a suburban diner. Known as David to his family and friends, he had a son who was 8 months old, and his girlfriend was pregnant with their daughter. They planned to marry in the spring.

Mr. White did not make it home. A 16-year-old gang member, drunk on cheap wine and seeking retribution for the stabbing death of a member of his crew, shot him with a .38-caliber handgun, piercing his heart and his right lung. Mr. White, who was unarmed and had no police record, was left to die in the street.

His killer went on to a prosperous life as a sports and marketing executive. He is Larry Miller, now 72, a former team president of the Portland Trail Blazers and the head of the Michael Jordan brand at Nike. He kept the secret of his murderous past for more than half a century, revealing it in a recent Sports Illustrated interview and a forthcoming book.

Mr. Miller wonders in the book how he became fortunate enough to leave his old neighborhood. But he never names his victim in an advance copy of the book viewed by The New York Times, and he spends little time reckoning with the devastating implications for Mr. White, who never got a chance to hold his daughter, to see his son become a high school basketball star, to spoil his grandchildren. Fifty-six years after Mr. White’s death, his family members say they have been blindsided again by Mr. Miller and left grieving anew, caught unaware that the magazine article and the book were going to be published.

A family member saw the Sports Illustrated article by chance online. Mr. White’s name was mentioned in the article, and Mr. Miller said he planned to reach out to the family. But relatives say they still have not heard from Mr. Miller. They are upset that he did not mention Mr. White’s name or details of his life in the book. Mr. White remains thinly drawn as an anonymous victim, a stranger, “another Black boy.”

A onetime Cub Scout, Mr. White had earned spending money as a youngster by helping shoppers carry their groceries home from the supermarket. He could be mischievous, too. He sometimes drove his sister’s 1960 Chevy, even though he did not yet have his driver’s license, and once, after an overnight trip, had to explain to his parents how he had suddenly obtained a basket of food from his grandmother’s house in Maryland. He got his job at the diner through the city’s Youth Corps program six months before he was killed, his parents said at the time, and wanted to become a chef.

At the least, the family would like Mr. White’s name and story to be inserted into Mr. Miller’s book before it is published, if possible. “Jump: My Secret Journey From the Streets to the Boardroom,” written by Mr. Miller with his eldest daughter, Laila Lacy, is scheduled to be published in January by William Morrow, an imprint of HarperCollins.

“You know his name, give him that respect, especially since you took his life,” said Mariah Green, an elementary schoolteacher in Philadelphia who is a great-niece of Mr. White’s.

Mr. Miller did not respond to messages on Thursday requesting a comment. Reached by telephone, his executive assistant asked a reporter to send her an email, which neither she nor Mr. Miller responded to. A representative for William Morrow, the publisher, also did not answer emails requesting comment.

Mr. Miller was arrested on the night of the shooting. He pleaded guilty to second-degree murder, was placed in a prison for young offenders and was released after four and a half years. He served five more years for a series of armed robberies. But in his 30s, he found ballast in his capsized life, earned a bachelor’s degree and a Master of Business Administration and began to climb the corporate ladder, hobnobbing with star athletes like Jordan and Derek Jeter and producing fashion shows that featured Miss Universe and Tyra Banks as models for the Jantzen swimsuit company.

He considers himself the beneficiary of redemption that is possible when corrections officials provide education and rehabilitation and hope for inmates instead of mere warehousing.

The Great Read

Here are more fascinating tales you can’t help but read all the way to the end.

Mr. Miller does express remorse in the book. He acknowledges that the killing was unprovoked and senseless, and that he did not know his victim or whether he belonged to a rival gang. His regret for the murder “would never ease — nor should it,” Mr. Miller wrote, adding, “I will forever mourn his loss.”

Writing the book, Mr. Miller says, began to free him from nightmares and migraines. He hopes it will help inspire youths to understand that a life’s troubled crossroads does not have to mean a dead end. But while Mr. Miller has been able to move forward, Mr. White’s family members say they find themselves handcuffed to the past.

Josaphine Hobbs, 75, the mother of Mr. White’s children, said she was so distraught at Mr. White’s death that she tried to climb into his grave at the funeral. She said she dropped out of nursing school to raise her young son and daughter as a single mother and was unable to claim Social Security survivors’ benefits for the children. And because she had not graduated high school, she soon lost a clerical job at an insurance company.

She has repressed so many memories of the killing that she can remember nothing of a man accused, a sentence handed down.

“I don’t think my mom ever got over that trauma,” said Azizah Arline, Mr. White and Ms. Hobbs’s daughter, now 55, who owns a day care center and lives in Pennsauken, N.J. “It changed the entire pattern of her life.”

Four years after Mr. White’s death, Ms. Hobbs married and had two more children. She resumed her career as a secretary. But a question continues to burn in her heart: What did Mr. White do to inflame such malice in Mr. Miller? She asks but knows the answer. Mr. White did nothing.

“David wasn’t in a gang; he didn’t get into fights,” Ms. Hobbs said. “He got shot going home.”

Mr. White’s eldest sister, Barbara Mack, now 84 and echoing other family members, said she did not understand how Mr. Miller was released from prison after serving only four and a half years for murder, even though he was a juvenile when he committed the crime.

“That shows that Black on Black crime, no one really cared,” Mrs. Mack said.

For years, she said, she avoided the West Philadelphia corner of 53rd and Locust Streets, where her brother died. It was too painful even for the family to discuss the killing. Hasan Adams, 56, Mr. White’s son, honored his father by giving his own eldest son, also named Hasan, the middle name David. Until he read the Sports Illustrated article last weekend, he knew only that his father had been shot while coming home from work.

“It’s mind blowing,” said Mr. Adams, a Philadelphia postal worker. “The furthest thing from my mind was that the killer of my father was a wealthy and successful businessman and he’s writing a book.”

When he tried to tell his wife, Mr. Adams choked up and couldn’t get the words out.

“I was scaring her,” he said.

Mrs. Mack, Mr. White’s sister, has written to William Morrow, saying that the revisiting of an “ungodly act reopens a wound, the hurt, the tears” of what happened decades ago. She wants the publishing company, and Mr. Miller, to know that her brother was not merely a stranger shot with no regard, but a teenager loved by his parents and four siblings.

Mr. White’s family says it wants something more than remorse from Mr. Miller. It wants some kind of atonement. A formal apology. A letter. A meeting with the family. A scholarship in Mr. White’s name. Perhaps some financial reparation for Mr. White’s children from the profits of the book.

In the Sports Illustrated article, powerful figures like Adam Silver, the N.B.A. commissioner, and John Donahoe, the Nike chief executive, praised Mr. Miller for disclosing his past. Mr. Silver said Mr. Miller’s experience “made him an especially supportive and understanding friend when it came to dealing with others’ foibles and mistakes.” He said he was amazed by Mr. Miller’s career, but was ultimately “left with a feeling of sadness that Larry had carried this burden all these years without the support of his many friends and colleagues.”

Mr. Donahoe called Mr. Miller’s story “an example of the resilience, perseverance and strength of the human spirit” and said he hoped it would “create a healthy discourse around criminal justice reform.”

Mr. Miller is to be commended for rebuilding his life, said Willie Gray, 79, a longtime friend of the White family and a former warden at Holmesburg Prison in Philadelphia. But, Mr. Gray added, “If he wanted to be truly redeeming, before he set pen to paper he would have reached out to the remaining members of the family and let them know how bad he felt and asked, ‘Can you find it in your hearts to forgive me?’”

Mr. Miller and Mr. White lived eight blocks apart in large middle-class families. Mr. Miller’s father worked at a factory that made drywall; his mother was a stay-at-home parent. Mr. White’s father was a self-employed painter and hung wallpaper; his mother was a nurse. Neither teenager liked school.

Mr. Miller describes himself as a straight-A student who found a sense of cool and belonging in a gang instead of in a classroom. Two years after the killing, he was named valedictorian of the 157 teenage inmates who received their high school diplomas at a correctional institution.

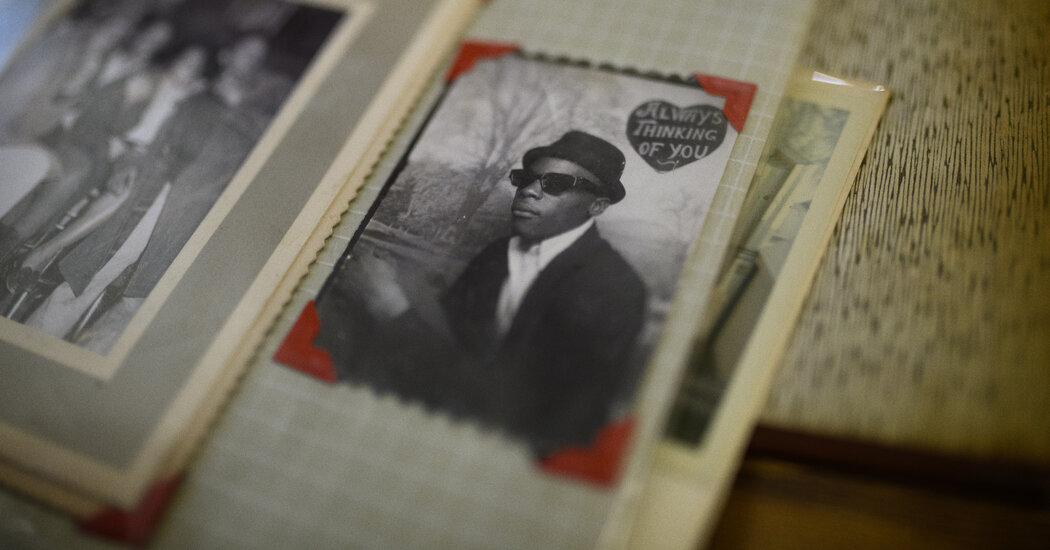

Mr. White did not graduate from high school, preferring to work. He was known for his sense of style — a fedora worn at a jaunty angle, sunglasses, sharply creased slacks, brogues known locally as “old man Comforts.” Mr. Adams keeps a photo of his dapper father on his phone.

“I always heard that he was so cool and nothing bothered him too much,” he said.

Mr. White also had what his eldest sister, smiling, described as a vocabulary like a profane jukebox loaded with the music of “maybe 500 curse words,” uttered with the same gleefulness with which he danced and sang to songs by the Temptations. “My Girl” was his favorite.

Before heading to work on Sept. 30, 1965, Mr. White stopped and bought two sweaters. As he came home that night, he encountered Mr. Miller and several other allies of the Cedar Avenue gang. Earlier that month, a member of that gang had been stabbed to death by a rival from the 53rd and Pine Streets gang. Mr. Miller was out for revenge.

Mr. Miller writes that he carried a .38-caliber handgun given to him by his girlfriend. He and three companions surrounded Mr. White on the corner of 53rd and Locust.

Mr. White pleaded that he was not in a gang and raised his hands. Mr. Miller shot him in the chest and kept walking, thinking to himself “that was one down” and that he was “on the hunt” for another rival gang member. It would be decades before he could come to terms with what he had done in killing “a boy who was just like me.”

Years later, as his criminal life became a corporate life, Mr. Miller says that he lost a job offer from the Arthur Andersen accounting firm after acknowledging the murder. After that, he says, he did not lie about it but omitted the truth. Until now.

Mr. White was pronounced dead at a hospital visible from his parents’ home. He was interred 20 miles away in Rolling Green Memorial Park in West Chester, Pa., buried near his parents, George and Pearl White, and an older brother, George Jr.

He died before all of them. His 75th birthday would have been Nov. 21.

“I never met the man,” said his daughter, Mrs. Arline. “That’s not fair.”

Sheelagh McNeill contributed research.