“It is a tremendous duty to ensure that Clotilda is protected, and the Alabama Historical Commission takes its role as the legal guardian of Clotilda very seriously,” Lisa D. Jones, the commission’s executive director, said in a statement. “The Clotilda is an essential historic artifact and stark reminder of what transpired during the trans-Atlantic slave trade.”

The Clotilda’s final voyage was undertaken illegally because Congress had banned the importation of enslaved people more than half a century earlier.

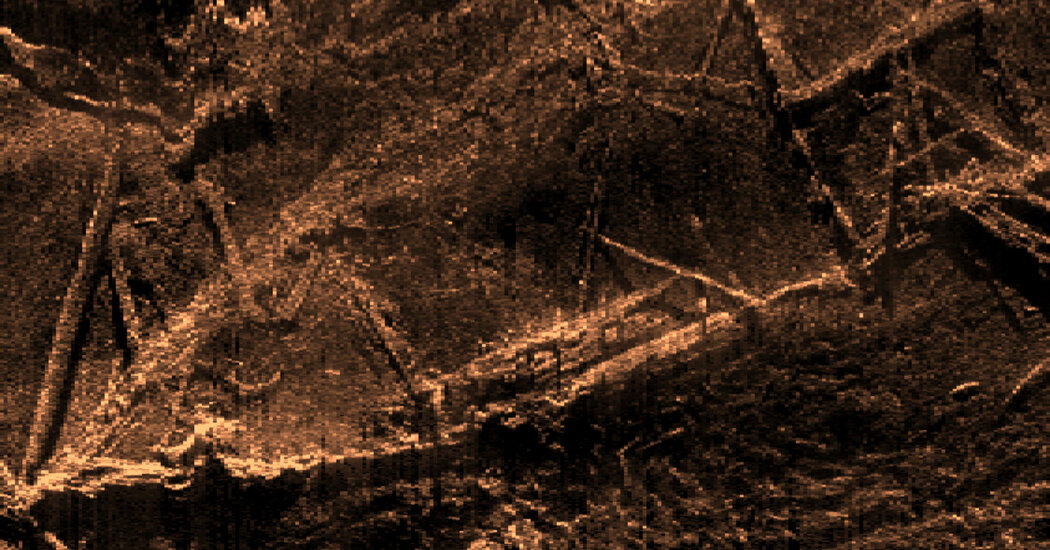

After the schooner arrived in Mobile and transferred the captives to a riverboat in July 1860, the Clotilda’s captain, William Foster, burned and scuttled the ship to hide evidence of his illicit trade, Dr. Delgado said. The ship has remained in the same spot in the Mobile River ever since, researchers said.

After the Civil War, some of the people who had been transported on the Clotilda asked their former enslaver, Timothy Meaher, who had organized and financed the voyage, to give them land, said Dr. Diouf, the author of “Dreams of Africa in Alabama: The Slave Ship Clotilda and the Story of the Last Africans Brought to America.”

When Mr. Meaher refused, the formerly enslaved workers bought land from him and others, Dr. Diouf said, and formed Africatown, where African languages were spoken for decades.

“It’s, of course, a story of resistance,” she said. “They, from Day 1, acted as a community and as a family and they continued to be very active after they became free.”

Joycelyn Davis, who lives in Africatown and is a descendant of Charlie Lewis and Maggie Lewis, who were enslaved on the Clotilda, said she hoped that archaeologists could find barrels and other items as well as DNA that could be linked to descendants.